How I came up with all this?

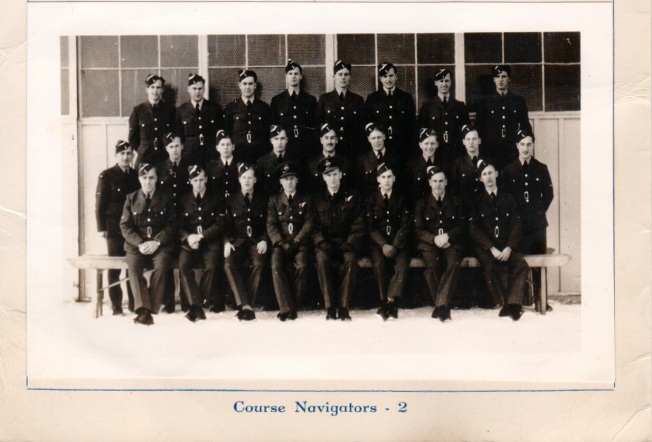

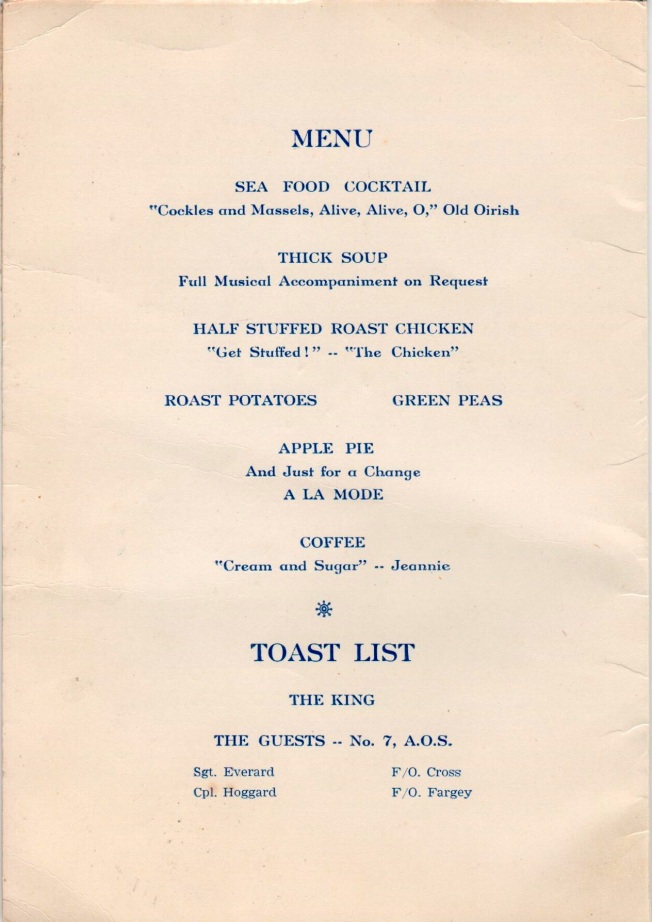

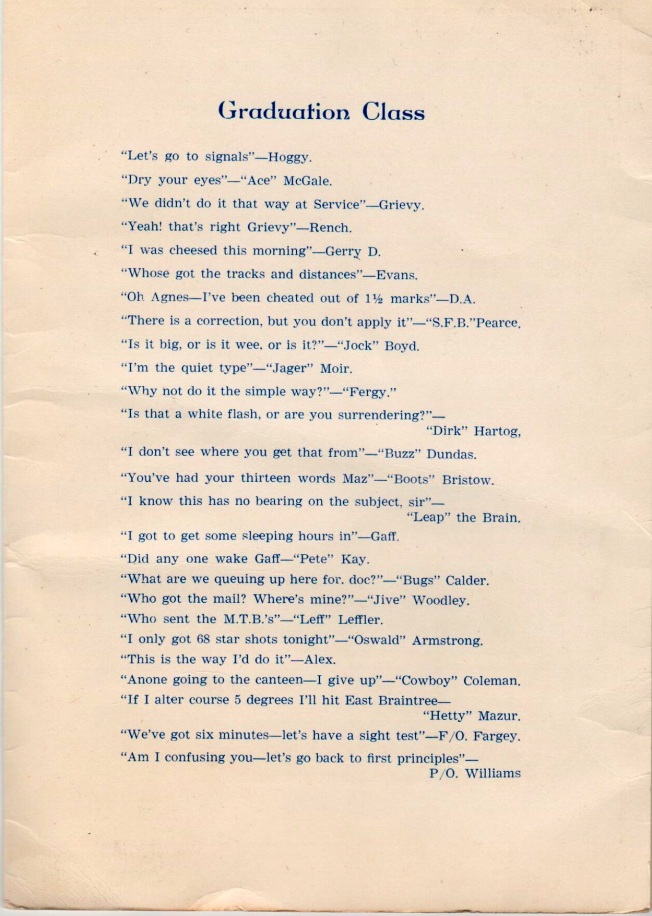

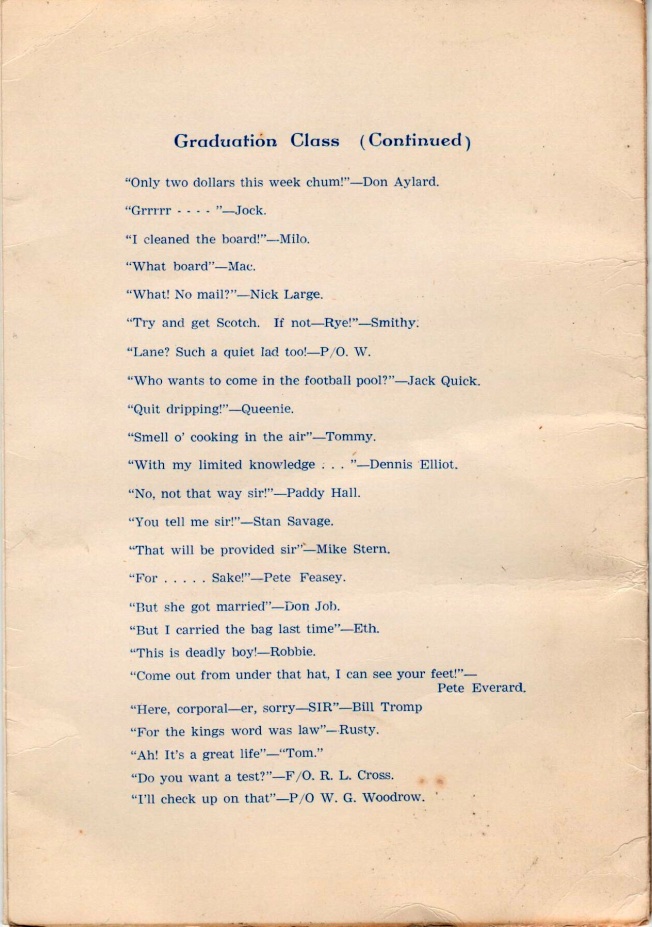

Bert was with No 4 Squadron but I was interested in the picture as it was taken at the same spot that my father’s photo was taken. Many years ago we visited that hotel so he could look around. He did further training in No 33 EFTS in Canada, Heaton Park Manchester, Lords in London, but I have no dates. He died 23 years ago and because my mother died and we are clearing her house lots of photos crossing the Canadian Prairie to Medicine Hat, Moose Jaw etc are emerging, Including a Graduation Dinner of 83 Navigators in Winnipeg- undated but includes photos of 2 classes of RAF graduates. Any info welcome

Anne

Reblogged this on RAF 21 Squadron and commented:

A follow-up to a comment left on this blog…

Bert was with No 4 Squadron but I was interested in the picture as it was taken at the same spot that my father’s photo was taken. Many years ago we visited that hotel so he could look around. He did further training in No 33 EFTS in Canada, Heaton Park Manchester, Lords in London, but I have no dates. He died 23 years ago and because my mother died and we are clearing her house lots of photos crossing the Canadian Prairie to Medicine Hat, Moose Jaw etc are emerging, Including a Graduation Dinner of 83 Navigators in Winnipeg- undated but includes photos of 2 classes of RAF graduates. Any info welcome

I am writing in reply to Anne’s request for information re Course 83.

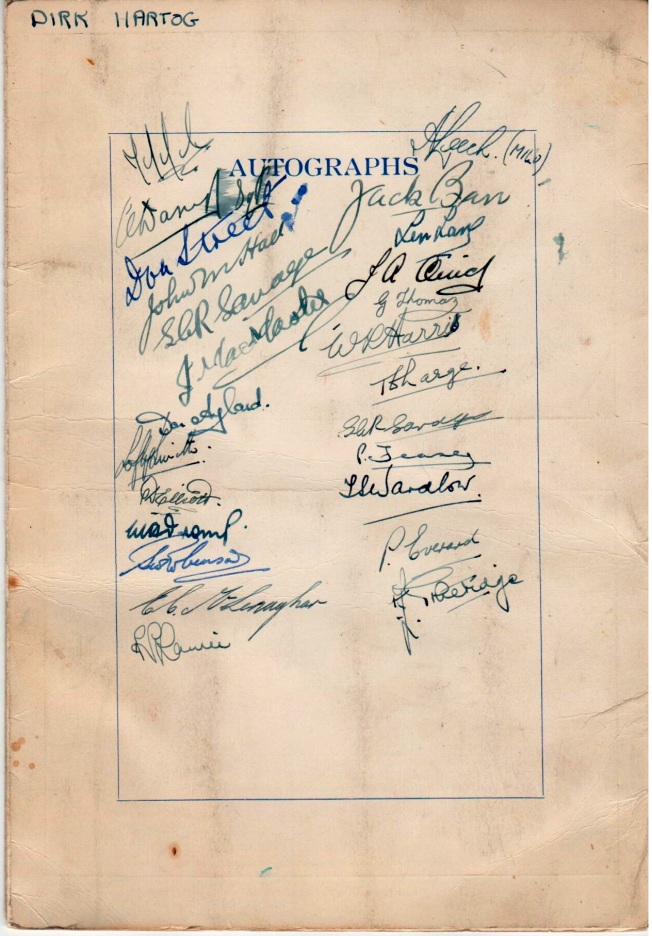

My father Stanley C.R.Savage was on that course and I see that he signed the back of the menu you have. From Dad’s log book I see that the course was completed at No 7 A.O.S. Portage La Prairie on 14th. Jan 1944, presumably the graduation dinner took place around that time.

I have a menu and set of photographs the same as yours and more of their travel across to Montreal area. On the picture in front of the aircraft, my father is in mid row, fourth from the left.

On returning to the UK Father served as air navigator with 100 squadron, he survived the war and left the RAF at the end of 1949.

Hope that this may be of some interest to you. At the moment I am attempting to put father’s RAF service into some order and context by creating a power point type presentation so that future generations can appreciate the effort and sacrifices that were made.

Kind regards

Ian

Once the PowerPoint is done, I can post it on the blog.

Thanks for your acknowledgment. It would be good to post it on the blog.

Regards

Ian

Feel free to contact when it is done.

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~nbpennfi/penn8b1TrainingPlan.htm

Training Plan

Months of hard work were in store for the many men who enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) to serve in the Allied cause. In order to ensure each member was placed in the position best suited to their capabilities and then, properly trained as such, the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) required that recruits pass through multiple levels of testing and schooling before they were posted.

The first step in joining the RCAF was contacting the local recruitment office. After signing up, a recruit was asked to report to a Manning Depot. At a Manning Depot, trainees were given a series of medical tests and issued uniforms. They practiced marching drills and performed guard duty until there was room for them at Initial Training School (ITS).

Designed to be difficult, ITS was used as an introduction to air training, and recruits that were not capable of serving to RCAF standards were quickly eliminated. Trainees were immersed in a five week basic training class that covered air force law, navigation, meteorology, aircraft recognition, the theory of flight, mechanics and, of course, discipline. Nine out of 10 men wanted to be trained as pilots and often a Link Trainer was a definitive moment in that decision.

Aircrew trainees graduated from ITS to a specialized school that matched their capabilities.

At the beginning of World War II, those destined to be air observers graduated from ITS to Air Observer School (AOS)1 for a 12 week course on aerial photography, navigation and reconnaissance. After AOS, trainees would move onto Bombing and Gunnery School (B&GS)2 for 10 weeks and then to Air Navigation School (ANS) 3 for another four weeks. In June 1942, it was decided that these duties were too much for one person and the position of air observer was broken up into two positions: navigator and air bomber.

Navigators could specialize in bombing or as wireless operators. Those training for the former were at Bombing and Gunnery School for eight weeks and then Air Observer School for 12 weeks. These men were qualified as both bomb aimers and navigators. Navigators who trained to specialize in wireless operations spent a great deal of time receiving training—28 weeks at Wireless School followed by 22 weeks at Air Observer School.

Men designated to be wireless operators attended Wireless School for a total of 28 weeks, becoming adept at radio work. They were also trained in air gunnery at B&GS for six weeks.

Recruits going into air bombing were trained not only to drop bombs accurately, but to assist navigators as well. They spent eight to 12 weeks at B&GS and six weeks at an AOS. Air gunners underwent a 12 week program at B&GS that included ground training and air firing practice.

Sgt E.M. Romilly, RCAF, W.H. Betts, RAAF, and J.A. Mahoud, RAF, practicing navigation techniques on board an Anson from the No 1 Air Navigation School, Rivers, Manitoba, 4 June 1941.

SOURCE: National Defence Image Library, PL 3740.

SOURCE: Wings Over Alberta website.

Air Observer Schools

Name Location Dates of Operation

No. 1 AOS Malton, Ontario 27 May 1940-30 April 1945

No. 2 AOS Edmonton, Alberta 5 August 1940-14 July 1944

No. 3 AOS Regina, Saskatchewan 16 Sept ember 1940-1 September 1942

No. 3 AOS Pearce, Alberta 1 September 1942-6 June 1943

No. 4 AOS London, Ontario 25 November 1940-31 December 1944

No. 5 AOS Winnipeg, Manitoba 6 January 1941-30 April 1945

No. 6 AOS Prince Albert, Saskatchewan 17 March 1941-11 November 1942

No. 7 AOS Portage la Prairie, Manitoba 28 April 1941-31 March 1945

No. 8 AOS Ancienne Lorette, Quebec 29 September 1941-30 April 1945

No.9 AOS St. Jean, Quebec 7 July 1941-30 April 1945

No. 10 AOS Chatham, New Brunswick 21 July 1941-30 April 1945

Bombing and Gunnery Schools

Name Location Dates of Operation

No. 1 B&GS Jarvis, Ontario 19 August 1940-17 February 1945

No. 2 B&GS Mossbank, Saskatchewan 28 October 1940-15 December 1944

No. 3 B&GS MacDonald, Manitoba 10 March 1941-17 February 1945

No. 4 B&GS Fingal, Ontario 25 November 1940-17 February 1945

No. 5 B&GS Dafoe, Saskatchewan 26 April 1941-17 February 1945

No. 6 B&GS Mountainview, Ontario 23 June 1941-Post War

No. 7 B&GS Paulson, Manitoba 23 June 1941-2 February 1945

No. 8 B&GS Lethbridge, Alberta 13 October 1941-15 December 1944

No. 9 B&GS Mont Joli, Quebec 15 December 1941-14 April 1945

No. 10 B&GS Mount Pleasant, PEI 20 September 1943-6 June 1945

No. 31 B&GS Picton, Ontario 28 April 1941-17 November 1944

Air Navigation Schools

Name Location Dates of Operation

No. 1 ANS Trenton, Ontario 1 February 1940-23 November 1940

No. 1 ANS Rivers, MB 23 November 1940-11 May 1942

No. 1 CNS* Rivers, MB 11 May 1942-15 October 1945

No. 2 ANS Pennfield Ridge, New Brunswick 21 July 1941-30 May 1942

No. 2 ANS Charlottetown, PEI 1 February1944-7 July 1945

No. 31 ANS Port Albert, Ontario 18 November 1940-17 February 1945

No. 32 ANS Charlottetown, PEI 18 August 1941-11 September 1942

No. 33 ANS Mount Hope, Ontario 9 June 1941-6 October 1944

*Central Navigation School

https://sites.google.com/site/nvquinnell/part2

Nevertheless, conditions on, and especially off duty were really good. We had all done around 70 hours day and 10 hours night flying and, I believe, nobody had failed.Our course finished officially in the first week of November, and shortly after, a train journey of only 400 miles took us to No. 5 Air Observers School at Winnipeg, Manitoba. I was armed with an Air Bomber Armament certificate and now it was to be a concentration on navigation. (I was also in possession of a Canadian Post Office Savings book which I’d opened with a deposit of 10 dollars. 9 dollars were later withdrawn, but I still have the book. What is the interest on a dollar over 60+ years?)

The airfield was partly civilian, and adjacent to the city. Winnipeg was the Provincial capital, built around the junction of two rivers, the Assiniboine and the Red, and was really “large”, with a population approaching 200,000. Yet it was bustling, with fine shops and monumental Victorian type civic buildings, bridges, trams and buses, cinemas, etc. There was, somewhere, a summer recreational area known as Winnipeg Beach. A complete change to the remoteness of Dafoe.

The Station was more compact than Dafoe but with a similar layout of runways. The barrack blocks were longer, and may have held 70 or more. They were also built on stilts, some 4 feet off the ground, with stairs up to the doors. The reason would soon be apparent. The accommodation would have been good, but we shared it with three dozen Australians and a number of New Zealand trainees. The latter were fine; it was the Aussies who were a boisterous menace and decided that Poms were fair game for irritation. A favourite prank was to wait until after “lights out” and we were dozing or asleep, then throw missiles in the dark at our beds, usually gym shoes or similar kit. Naturally there would be retribution in kind until someone put the lights on and order was restored. A wild bunch, a couple of whom got into trouble for upending a young “WAAF” in the games room, after some banter and argument as to whether she was wearing regulation or fancy knickers.

For the first three weeks it was classroom work, mostly navigation, using a sextant, which involved astronomy for star “shots”, compass plotting on charts etc. and some meteorology. There were the PT classes, swimming, and Stick Hockey. It may have had another name, but was a very fast version of hockey on a small indoor pitch (a concrete floor). Instead of a ball there was a fairly heavy circular felt pad, 6 inches across and 1 inch thick with a 2 inch hole in the centre, a bit like an ice hockey puck. The stick was quite straight and, though one could hit the pad, to control a shot it needed to be in the central hole, which gave it considerable speed. I disliked many team ball games, but Stick Hockey was fast fun.

When off duty there were no problems about going into the city, after signing at the Guard Room. The centre was only 3 miles, by frequent buses, but the attractions were rather limited to window shopping in the main street, Portage Avenue, cinemas, and the minimal sightseeing…

Well wrapped up I could happily spend a quarter hour on a bridge watching the wide and fast flowing Red River tumbling beneath. There were numerous fairly cheap snack bars, which we used as meeting places. Canadian Provinces were rather like American States and created some of their own laws. Alcohol was discouraged in Manitoba by a rationing system. We, like the rest of the population, could get a card with coupons allowing one or perhaps two half pint bottles of beer a day (wines may have been a bottle a week and spirits a bottle a month), purchasable in a “pub” – a dreary little one room shop with a counter and a few stools. No adverts, pictures, music, or comfort. This did not apply in camp however, where, as I recall, consumption was restrained by price and probably a limited time when the bar was open. It was outside a town bar that I met a young French Canadian and his girlfriend one evening and accepted an offer to go to their nearby flat for a drink. After some coffee and general conversation, talk turned to the local hospital, where they were making a visit, and thought I might like to come along. It was all rather odd and it took me a few minutes to realise that their “hospital” was a house where they got drugs or injections of drugs. Perhaps they got a free dose for every new customer they introduced, but once outside on the street where I could merge with other pedestrians I made quick excuses and disappeared into the night.

Winnipeg was a pleasant city to walk round, with parks, some fine municipal buildings, and the one bridge in particular, from which you could see the confluence of the Assiniboine and Red rivers. The latter originated in the States, and both rivers flowed North into Lake Winnipeg, 30 miles North of the city, and which then extended 300 miles northwards.

It became progressively colder from our first day with temperatures dropping to below freezing, and within a fortnight snow fell heavily to a depth of 2 to 3 feet. It was cleared on streets and on the camp roads. The raised barrack blocks were easily accessed by their steps, and snow was pushed under the buildings by the clearing machines. Soon the daytime temperatures dropped to minus 20 F., and lower at night. For most of us this dry cold was a new experience and not unpleasant when wrapped up, though I stupidly took a glove off when posting a letter and got a blister on my thumb when it pressed against the metal box. Snow was a novelty to the Australians who revelled in snowball ambushes, even to the extent of introducing one into our hut, much to everyone’s fury. Winnipeg’s aircraft were again Ansons, but a later Mark V version with a small perspex dome in the roof from which to take star “shots”. No doubt there were other modifications. I cannot recall how a crew was made up, but all the pilots were civilians, not RCAF, and it seemed quite exceptional. Again there may occasionally have been a Wireless Operator hidden in a niche, and one, or usually two, trainee navigator/air bombers. The heating was a crude and inefficient hot air system which, when it was up to minus 35F outside, maintained a temperature a little above freezing inside. It was not unknown for a flight to be curtailed at half time when a temperature became so low it impeded work even though one wore woollen mitts and a padded flying suit.

Every flight involved navigation and some bombing at “high level”, ie. near 8 or 9,000 feet I think. Bombing targets were 50 miles NW of Winnipeg and 100 and 200 miles to the West. Generally flights covered 400 to 500 miles and lasted 3 hours or more.

On my first flying day I did two flights totalling over 6 hours, one early morning, the other at night. Routes were planned to avoid trespassing into North Dakota, 40 miles South, and not to go into Saskatchewan to the west, which was in a different time zone. A great help to navigation at night were some small towns, where a local radio mast would have a light transmitting the initial letter of the place name in Morse code. I guess it was primarily to assist civilian flyers but was invaluable – even if an unfortunate surprise on the odd occasion.

All flying maps were based on the nationally available sheets at a scale of 8 inches to one mile (approx. 1/ 500,000), colour contoured at 1000 ft. intervals, and fairly detailed. Each covered an area of 175 X 150 miles and most had been revised in the last 3 -5 years, though one or two were thirty years old. For military use they were overprinted with all RCAF airfields and their details, civil air corridors, and long distance radio range beacons, their call signs and weather report stations. There were a surprising number of airfields, eg. 12 on the Brandon-Winnipeg sheet, though on that to the east there were only 2 civil ones.

Only twice did I fly across that eastern area, Kenora-Hudson; thousands of square miles of wilderness comprising pine forest with hundreds and hundreds of lakes, ranging from a quarter mile to 50 miles long. An even longer lake, “Lake of the Woods” (Ph.10 :2), went South into Minnesota. This snow and ice covered desolation was astonishing, and happily left behind on each trip, remembering pilots discussing an accident a couple of years earlier when an aircraft crashed on a lake and went through the ice, never to be recovered.

On the easterly flights bombs were usually dropped on the first leg, at the ranges on Lake Manitoba, 60 miles NW of Winnipeg, or Dauphin Lake, another 100 miles on. At night the targets were lit and there must have been some ground system for recording the accuracy of strikes, relayed to base or the pilot but not, I think, to the air bomber, who learned the results later.

Day flights were somewhat routine. Much of central Canada is relatively flat at an altitude of 1000 to 1500 ft. with a few areas of “mountains” rising to 2500 ft. and hardly hazardous. Useful navigationally, as were small towns (often more like hamlets) on crossroads. Others appeared identical, especially since all hedges, fences etc. seemed to follow the N/S and E/W rules.

Night flying could be difficult, establishing one’s position by sextant shots on stars. Now I have no idea now how it was done with the aid of star tables, but I remember that vision of stars was always impaired when the common Aurora Borealis was intense, however beautiful it might appear from the ground. It also had a curious effect upon the propellers of the plane, as showers of “sparks” clung to the tips forming a sort of halo round each engine. I believe it also interfered with wireless communication.

One night, with no Aurora active, a first leg to Brandon had been completed, and a short second one was to take us to within 20 miles of the Saskatchewan and North Dakota border, when the port engine started sprouting some bluish flames, intensifying and turning yellow. When they got larger, after the pilot had switched the engine off, we were told to put our parachutes on, await an order to open the door, and jump. There were three of us, including the pilot, who was reducing height a bit, from the common eight to ten thousand feet, and thankfully there were no lakes below. Fully kitted, and standing by the door, we saw the flames shorten, gradually turn to sparks and then die away. With relief, the pilot, who was in radio contact with some ground station, told us to sit down and produce a course to Winnipeg – though I suppose he knew the way well enough – and we returned using only one engine. Yet I’ve always been a little bit disappointed that I didn’t have the experience of a jump, though a daytime one would be more sensible and pleasurable.

During time at Winnipeg it was a common practice for citizens to invite trainees to their homes on Sundays for afternoon tea, and it was done by giving a name and telephone number that was put on a notice board in the Welfare Officer’s room. Usually the invitations came from first generation immigrants of the 1920’s or early 30’s, many of whom seemed to be Scots. I went to two houses, the first on my own. They were second generation, with a small boy, and very Canadian, though a father had been English. I think it was because of that most of the conversation dealt with conditions in Britain and comparisons with Canada. I can’t remember the meal, but having expressed curiosity about the central heating system was given a tour. A fairly new solidly built house (not clapboard), the sole heating was by hot air ducts from an oil fired boiler in a small ventilated basement. The hot air was pumped from a grill high in the wall of each room and returned via a low level grill, unlike anything I had seen before. As everywhere, including our barrack blocks, the temperature was kept to at least 70 degrees F. and, while it was in the minuses outside, it always seemed excessively hot within.

On the second occasion two of us accepted an invitation to the house of an elderly couple. I think my companion was a Scot; certainly the hosts were Scots who had, as always, retained unaltered homeland accents although they had emigrated decades before, when the husband had qualified as a doctor. Now retired, he was involved with the Canadian Red Cross or something similar.

I recall the invitation was to afternoon tea , and we had some difficulty in getting to the place, a detached house in a suburb reached by buses and walking. Consequently we were a little late but soon settled into the usual conversation about Britain/Scotland. (Now I cannot understand why we didn’t ask questions about Canada. Perhaps it was a reluctance to display ignorance, or to enter into any social or political territory). Anyway the afternoon passed pleasantly, with sandwiches, tea, and cakes, and finished unexpectedly with a further invitation, to visit them for Christmas Day dinner. This would be in a week’s time, and we both, without thinking ahead, accepted.

We left about 5.30 to walk for a bus, while it snowed lightly, and got dark

Disgracefully, on the 22nd, we sent a message with some excuse as to why we could not be with them on Christmas Day, though it was simply that it seemed it would be more fun in the camp. An act of stupid selfishness which has haunted me down the years ever since. Even though long dead….perhaps their ghosts remember.

A half dozen more flights and the course finished. The last two were night bombing trips on which I was air bomber and, according to the Log Book, also did “contact navigation and S/R”. I don’t now know what these mean or entailed. The final flight was on the night of the 23rd. Dec.

In all there had been about 30 hours of day and 6 hours of night flying, half as first navigator and half as second, with an additional 7 hours of night bombing. Altogether there were 15 flights, each with a different pilot and a different Anson, for a pilot kept to one aircraft. So, with almost 100 hours of day and 23 hours of night flying Canadian training was coming to an end. During the non-flying time of the 7 weeks at Winnipeg we had been kept fully occupied. There were classes on navigation – theory and practical – on meteorology, aircraft recognition, on the Mk. 9 bombsight, and signalling. The latter was primarily keying Morse, and some Aldis lamp work. Towards the end there were examinations and it was the results of these, plus marks obtained for navigation and bombing during flying, that determined the issue of the coveted “Wing”.

On the recreational side there had been the usual PT, some running, which was not particularly pleasant in the wintry conditions, and I opted for swimming and, surprisingly, for stick (or floor) hockey. An ice rink was also available for the adventurous.

Off duty there were the usual cards, darts, bowling, and other more boisterous team games for those so inclined. One could be assigned to a guard duty or similar but, because of the numbers it was a rarity. I don’t think it was weekly but occasionally a dance was held on a Saturday night.

A church Service was held on Christmas Eve, but as always in Canada, church attendance was not compulsory – unlike the UK. The Australians ensured an early and noisy start to Christmas Day yet otherwise must have been remarkably unobjectionable since I remember nothing else about them over the period.

I had received letters from home and friends fairly regularly while in Canada and two or three arrived for Christmas, though I don’t recall cards. (Presents would have been hopeless but I had shopped already to take some back to the UK). Nothing special happened on Christmas morning except the muted excitement and anticipation about the Dinner and afternoon entertainments. Nobody was disappointed. An enormous meal, with soup, the traditional turkey etc. pudding and fruit, accompanied by beer, and all served by Officers. It was, of course, not just for trainees but included all the lower rank staff, men and women, on the Station. I think NCO’s had their own mess room, as did the Officers, who would have eaten later. Dinner had been preceded by an address by the CO, making a rare appearance, and outlining the afternoon events. No doubt they were fine, including sketches, songs etc. with people from town, but it’s now a haze – perhaps the beer!

Immediately after Christmas the Course results were announced, and on the 27th the CO presented us with the “B” Wings and Sergeant stripes, the culmination of a year of work. Also a new beginning – no longer the lowly “erk” but someone with a title and an astonishing jump in pay to 13 shillings and 6 pence a day.

Around midday we returned to the billet, sewed our stripes and brevets on working and best uniforms, and waited for the afternoon group photograph. In this there are 22 of us and 2 navigator instructors, P/O Howarth and F/O Moore. Of the 22, I think 3 were recommended for Commissions, of whom I only recall Warren, the older, serious person. I do remember that on my pass certificate Howarth had written “Untidy and unconventional – not recommended for a Commission.”

Looking at the photo now, Pickering still comes to mind with his curious habit of lying on his bunk each evening and learning a half dozen new words and their meanings. I was friendly with Threadgold, but not O’Donnell, a brash Irish oddity who (I was told much later), died in North Africa, after falling down the steps of an air raid shelter.

We had been told that our next stop would be Halifax, Nova Scotia, to await a ship back to the UK. Halifax was some 1700 miles away and we had to be there by January 4th or 5th, something like that. Meanwhile we could stay and wait for the 2 day train journey, or have leave to go beforehand, individually, with a special train ticket allowing breaks in the journey. An enticing idea, and we would be paid in advance, but hardly anyone took it up. Ray Parslow had sent me a photo of himself at Niagara Falls. They looked as impressive as the tales I’d heard so Niagara was my prime port of call. Ray had by now returned to the UK so no chance of seeing him.

It may have been something to do with the ticketing or the railway routes, or simply lack of knowledge on my part, but the route taken wasted a lot of time.

The first leg was Winnipeg to Montreal, a distance of 1300 miles. I must have left early on the 28th to book into a small hotel on the afternoon of the following day. I dumped my kitbag, and wandered into town. I did not like it. After the friendliness of Winnipeg, the people of Montreal seemed almost hostile. I was unmistakably British, with limited school French, but they would only speak French though virtually all were bilingual. After two or three hours, and a meal I went back to the hotel, shortly to be accosted by a short middle aged man in a smart dark suit. This was in the hotel lobby, and he had come down the stairs with a young dark haired girl. In English he made a proposal concerning the girl which clearly indicated that she was a prostitute and he her minder. Escaping their clutches I retreated to my room and next morning set off for Toronto, a mere 300 miles but retracing my footsteps westward.

http://www.cambridgeairforce.org.nz/John_Christie.html

John CHRISTIE

Serial Number: NZ4212829

RNZAF Trade: Air Observer

Date of Enlistment: 24th of October 1942

Date of Demob: Unknown

Rank Achieved: Flight Sergeant (at least)

Flying Hours: Unknown

Operational Sorties: At least 13 (with No. 75 (NZ) Squadron)

Date of Birth: 12th of October 1923

Personal Details: Nothing is yet known about John Christie’s personal life.

Service Details: John Christie enlisted at RNZAF Station Ohakea on the 24th of October 1942, as an Aircrafthand (ADU), as a member of the Aerodrome Defence Unit there. However he was destined to be trained as an Air Observer and so John departed New Zealand onboard the ship Monticello on the 1st of April 1943, headed for Canada.

John trained at No. 5 Air Observers School in Winnipeg, as a member of Course 76N. He graduated the course on the 29th of September 1943.

It’s not certain where John went to next but certainly he went to England as he was posted to No. 75 (NZ) Squadron, a heavy bomber squadron, by August 1944, as the navigator in the crew of Pilot Officer John Rees Layton DFC(NZ425914, Captain).

Also in his crew were

Flying Officer Louis Thomas Freidrich (NZ428060, 2nd Pilot)

Pilot Officer Clive Woodward Estcourt (NZ391045, Air Bomber)

Pilot Officer Ta Tio Tuaine Nicholas (NZ425658, Wireless Operator-Air Gunner)

Flight Sergeant David Onslow Light (NZ4212848, Mid-Upper Gunner)

Flight Sergeant Leslie Dixon Moore (NZ421327, Air Gunner)

Sergeant F. Samuel RAF (Flight Engineer)

The operations that John Christie is known to have flown with No. 75 (NZ) Squadron, in the crew above, as as follows:

Date

Avro Lancaster

Target

Note

3 Aug 1944

HK575 AA-

V1 Flying BombStore at L’isle Adam, France

Daylight Op

4 Aug 1944

HK756 AA-

Oil Refinery site at Bec-d’ Ambres, France

Daylight Op

8/9 Aug 1944

HK600 AA-

Oil/Fuel site at Foret de Lucheux, france

Night Op

9/10 Aug 1944

HK600 AA-

V1 flying bomb launch pads at Fort d’Anglos, France

Night Op

11 Aug 1944

HK600 AA-

Rail marshalling yards at Lens, France

Daytime Op

14 Aug 1944

HK600 AA-

German troop positions at Falaise, Normandy Battle Area, France

Daytime Op

15 Aug 1944

HK600 AA-

St Trond Airfield

Daylight Op

16/17 Aug 1944

ND782

Port and Industrial area, Stettin, Poland – on the border with Germany

Night Op. Engaged Junkers Ju88, Rear Gunner Les Moore claimed it as damaged

29/30 Aug 1944

ND904

Port and Industrial area, Stettin, Poland – on the border with Germany

Night Op

31 Aug 1944

PB418

V2 Rocket Site, Northern France

Daylight Op

8 Sep 1944

PB418

German field positions between Doudeneville and Le Havre

Daylight Op

10 Sep 1944

HK576

German field positions between Le Havre and Montivilliers

Daylight Op

12/13 Sep 1944

PB418

Frankfurt, Germany

Night Op

Today: Unknown

Connection with Cambridge: Apparently from Cambridge prewar

Thanks to: Errol Martyn, Don Simms and Wayne Mellor for helping with information on this airman. Operations and crew information is sourced from the No. 75 Squadron Association History from the chapter compiled by Squadron Leader Ron Macfarlane AFC, RNZAF (retired)

____________________________

http://www.bombercrew.com/HCU/oneil.htm

Flying Officer Jim O’Neil RCAF was born on July the 28th 1921 in London, Ontario.

After enlistment and basic training Jim attended No. 5 Air Observer School from August 22nd 1943 to January 14th 1944 based in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Jim graduated at the rank of Sergeant as a qualified Air Navigator having flown nearly 100 hours in Avro Anson Mark I and II aircraft.

On posting overseas he attended No 7(O) Advanced Flying Unit Course No. 95 (RAF Bishops Court) from August the 9th 1944 to September the 3rd 1944 also on Ansons. Receiving commission as a Flying Officer, Jim joined the Sumner crew in September 1944 at No. 20 OTU as their Navigator. The crew always had great confidence in Jim’s abilities as their Navigator knowing that he kept them plotted on course and on track about the skies. At the time of Jim’s service Gee and H2S were available as plotting tools and Jim was proficient in the use of these navigational electronic aids and airborne radar. Jim’s wit and sense of humour was exceeded only by his skill and ability in the art of aerial navigation and he was a valued member of the Sumner crew.

*I love it…….. Memories………..Memories*

*Joe Farrugia* *Malta GC*

Want to share those memories a little?